|

Let's talk about beads, shall we? Beads are good. I like them. They are shiny...

0 Comments

I've mentioned before that I'm starting to mentally categorize historic hats by basic shape: cylinders, cones, helmet or dome, halo or diadem etc. One of the things that I find interesting is that I keep seeing 'intersection points' where two cultures with two different hat shapes come into contact, borrow from each other and you get a sort of hybrid of the two shapes.

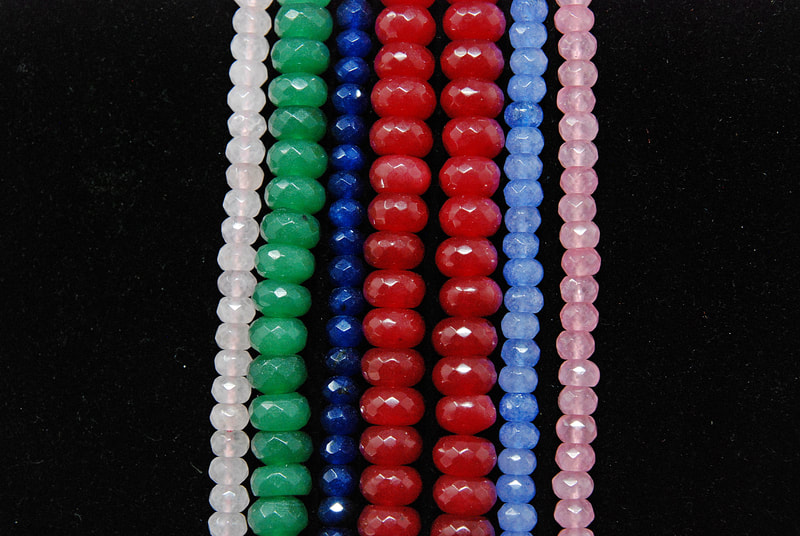

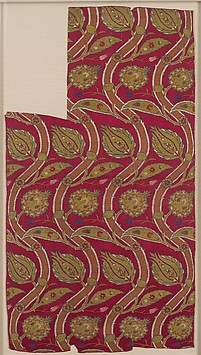

Today's post is a Caftan Project update. The next post will be about some studio experimentation with Byzantine hat shapes and an Etsy update and then in the next I'll talk about the bead show and how to shop for period-appropriate beads and gemstones. ?Caftan book update: two types of pattern pieces Lots of people think about sewing as being 'simple': an easy thing to do. (And there are lots of reasons why, many of those reasons going back to the idea of 'women's work', but that is a rant for another day...) In reality 'sewing' is a set of complex tasks with pattern drafting and fitting as arguably the most complex. Basically you are taking a flexible, functionally 2-dimensional object, cutting it into irregular shapes, connecting those pieces into a 3-dimensional object, turning it inside out and expecting it to fit a complex moving human body in a way that is functional, comfortable and beautiful. It's a complex engineering task when you break it down that way and one of the biggest obstacles to working with historical patterns is that they are based in completely different mindsets compared to modern sewing techniques and until you can wrap your brain around how the historical tailor thought about how fabric should be cut to fit a human body, its all chaos. Basically you have 3 different ways of thinking about patterning. One: the modern way: this is how most of the clothes in your closet are made and it developed in Europe beginning in the 14th century and the biggest signifier of this method is the curved armschye, that is, arm's eye. This developed when a very close fit began to be seen as more important than cutting patterns without wasting fabric. That is a big long complicated subject that is definitely not why you are here on this website so I won't go down that road, even though it is fascinating. But here are some cool links for Youtube: Bernadette Banner: in this video she is working historical patterns from Janet Arnold https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Voe8lQFjiUM Morgan Donner: drafting a kirtle https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yED06QFK2Q4 Modern Maker: this is a gallery of a few things made by my friend Matthew Gnagy in this patterning style. His books are amazing. https://themodernmaker.net/gallery-17-century-clothing Prior to the development of that kind of patterning, you could roughly divide patterning methods into two types. And you can't always tell which method was used just looking at the garment. It's actually about what is going on in the pattern maker's brain. Essentially, were they thinking about their raw materials as woven fabric, essentially an endless narrow rectangle? Or as irregular shapes that have to be pieced or shaped into a complete garment such as animal skins and wool felt? (You can check out the link in the last blog post to the database of skin garments if you want to see some really cool examples). The Mongols are the most influential culture in Central Asia to still be conceiving of clothing as pelt/hide/felt-based until late in the medieval period. The classic book Cut My Cote was my first introduction to this concept. And just today I spent awhile diving down a research rabbit hole with a friend looking at methods for recreating a hat that we are positive was felted, we just weren't sure how. (We have theories now...) So we went wandering on YouTube and found the perfect video to show you exactly how different the felting midset is. For weaving, you create string and interlace vertical and horizontal threads. Felting is entirely, completely different. You take the wool fibers off the animals and clean them. They have a structure like human hair, with microscopic scales. If you apply a combination of moisture, heat, agitation and an additive like soap (modern) or whey (traditional), the fibers permanent interlace and mat together to form a sheet of fabric or a three dimensional item such as a tunic or hat. The resulting fabric is really warm, but doesn't have a lot of tensile strength. You fluff up the fibers, letting them lie in all directions. You roll them up in an old felt, called a 'mother felt' or in modern times a tarp. Apply friction and agitation, sometimes by dragging behind a horse. Eventually, the fibers bind together into whatever shape you choose. You can alter the shape as you go. This video is of traditional feltmakers in Iran. They aren't showing you much of the agitation portion of the process, but they do show in detail how a tunic is made without any seams or sewing at all. Even if you only watch the first few minutes of it, you will see a completely different methodology for how to create a garment. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-WW39owXTE&fbclid=IwAR1FPhIxFdFewjnupdrLFCegmhBEC0etz7ZkURKZRaveHNhedXJbDtl7kSI Most of the cultures that created caftans thought of their materials as fabric; long narrow rectangles to be cut into geometric pieces and assembled with minimal waste. But as I had the opportunity to travel and get a close up view of many of these extant garments, there was a problem. Yes, rectangles and triangles and weird polygons under the arms were everywhere, cut symmetrically and systematically. But when you get really close to a lot of these garments, you start to see weird random pieces that appear out of nowhere. They seem to be added sort of ad hoc, not symmetrically, just wherever. It took me a remarkably long time to understand what was going on. Here's the thing: textiles produced by machinery really are endless rectangles with perfectly straight edges. But handwoven textiles are not. Every horizontal row of weft thread gets passed along by human hands, packed into place, pulled firmly along the edge and sent back in the opposite direction. And humans are not machines. There are variations not just in the width of a length of fabric, but also in how tightly packed each row is and good quality fabric has consistently packed rows. But even high quality handwoven fabric still has variations. Combine that fact with the expense of fabrics, particularly luxury fabric and people did whatever they had to do to get a complete garment. The conservator's report on the Caucasus caftan is hysterically funny to me because the brocade woven trim is of pretty terrible quality and the conservator's tone is one of indignation at just how uneven and badly woven it is. The theory is that the fabric may have been woven by indigenous weavers according to only a description of luxury foreign fabric seen by a high ranking member of the community and that it was woven on a tight deadline. Basically, the special occasion was almost there and the king was literally or figuratively standing in the weaving room yelling, "Weave faster!" So the motif starts out as evenly spaced circles and as the weaving progresses gets noticeably drawn out into extended ovals because the rows weren't being consistently packed. That results in the pattern repeats being inconsistent. So what we are seeing with all the weird piecing in the Ottoman caftans and other period caftans is that the tailor conceives of the fabric as being IDEALLY rectangular. And to compensate for the reality that it is not, uses irregular piecing to make the ideal geometric shapes. Basically, if the pieces making up each section (like the rectangle for the front left side, for example) aren't complete due to weaving issues or scarcity, the tailor adds pieces of whatever size and shape necessary to complete each section. Then the sections are sewn together. So when you are looking at the pattern diagram for an extant caftan there are two types of pattern pieces. There are the major pieces: large, structural, symmetrical, regularly geometric, cut on grain, and generally repeated from one caftan to the next. Some examples include rectangles or wedges for fronts, backs and sleeves, and triangles or wedges for gores in the sides or front. The second type are small, asymmetrical, frequently cut without regard to pattern or grain line, and frequently unique to the particular caftan. [At first glance you might think the gussets under the arms are in the second category, but they are actually in the first. Because while they are small and frequently cut without regard to grain, they are functional, necessary and symmetrical on the two sides of the garment] So the question becomes, when you recreate a garment, are you obliged to include the second category? These pieces only exist because of scarcity, or a 'defect' or irregularity in the fabric. All fabric of the time, all hand-woven fabric has irregularities. It's important to understand the strategies that were used to compensate, both to understand what you are looking at and as a tool for when you are confronted with similar problems in your own projects. However, because the second type of pattern pieces do not effect the fit, shape, drape or function of the garment, I don't see a compelling reason to include them unless you are deliberately recreating a particular garment. So for the caftan project, I plan to include these pieces as they occur in the individual garments but I don't plan to start making random patchwork a part of my general garment production strategy because it serves no useful purpose. I hope this provides some food for thought, please let me know what you think in the comments. |

Archives

February 2020

Categories

All

|