|

Let's talk about beads, shall we? Beads are good. I like them. They are shiny...

0 Comments

I've mentioned before that I'm starting to mentally categorize historic hats by basic shape: cylinders, cones, helmet or dome, halo or diadem etc. One of the things that I find interesting is that I keep seeing 'intersection points' where two cultures with two different hat shapes come into contact, borrow from each other and you get a sort of hybrid of the two shapes.

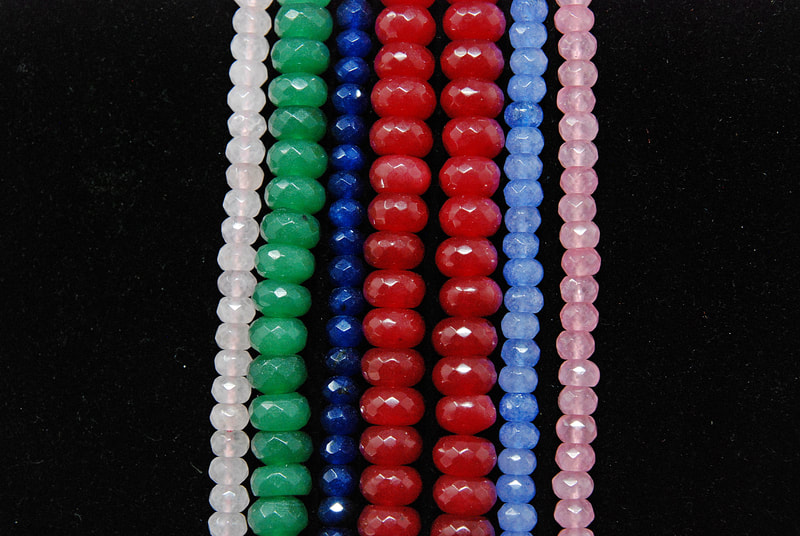

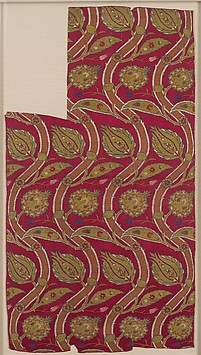

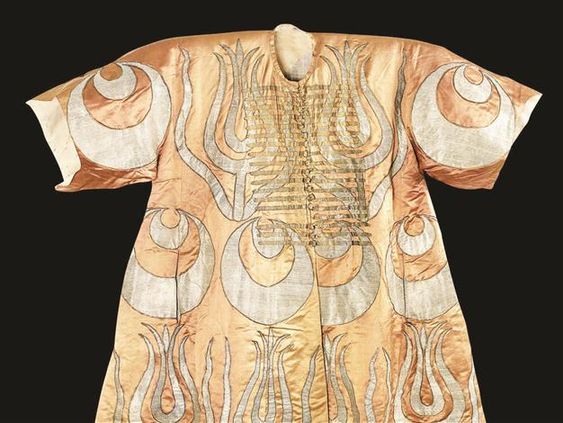

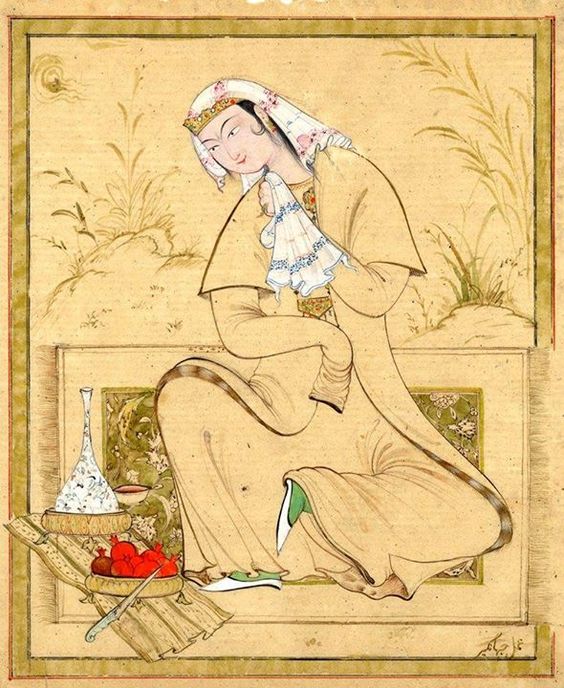

Today's post is a Caftan Project update. The next post will be about some studio experimentation with Byzantine hat shapes and an Etsy update and then in the next I'll talk about the bead show and how to shop for period-appropriate beads and gemstones. ?Caftan book update: two types of pattern pieces Lots of people think about sewing as being 'simple': an easy thing to do. (And there are lots of reasons why, many of those reasons going back to the idea of 'women's work', but that is a rant for another day...) In reality 'sewing' is a set of complex tasks with pattern drafting and fitting as arguably the most complex. Basically you are taking a flexible, functionally 2-dimensional object, cutting it into irregular shapes, connecting those pieces into a 3-dimensional object, turning it inside out and expecting it to fit a complex moving human body in a way that is functional, comfortable and beautiful. It's a complex engineering task when you break it down that way and one of the biggest obstacles to working with historical patterns is that they are based in completely different mindsets compared to modern sewing techniques and until you can wrap your brain around how the historical tailor thought about how fabric should be cut to fit a human body, its all chaos. Basically you have 3 different ways of thinking about patterning. One: the modern way: this is how most of the clothes in your closet are made and it developed in Europe beginning in the 14th century and the biggest signifier of this method is the curved armschye, that is, arm's eye. This developed when a very close fit began to be seen as more important than cutting patterns without wasting fabric. That is a big long complicated subject that is definitely not why you are here on this website so I won't go down that road, even though it is fascinating. But here are some cool links for Youtube: Bernadette Banner: in this video she is working historical patterns from Janet Arnold https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Voe8lQFjiUM Morgan Donner: drafting a kirtle https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yED06QFK2Q4 Modern Maker: this is a gallery of a few things made by my friend Matthew Gnagy in this patterning style. His books are amazing. https://themodernmaker.net/gallery-17-century-clothing Prior to the development of that kind of patterning, you could roughly divide patterning methods into two types. And you can't always tell which method was used just looking at the garment. It's actually about what is going on in the pattern maker's brain. Essentially, were they thinking about their raw materials as woven fabric, essentially an endless narrow rectangle? Or as irregular shapes that have to be pieced or shaped into a complete garment such as animal skins and wool felt? (You can check out the link in the last blog post to the database of skin garments if you want to see some really cool examples). The Mongols are the most influential culture in Central Asia to still be conceiving of clothing as pelt/hide/felt-based until late in the medieval period. The classic book Cut My Cote was my first introduction to this concept. And just today I spent awhile diving down a research rabbit hole with a friend looking at methods for recreating a hat that we are positive was felted, we just weren't sure how. (We have theories now...) So we went wandering on YouTube and found the perfect video to show you exactly how different the felting midset is. For weaving, you create string and interlace vertical and horizontal threads. Felting is entirely, completely different. You take the wool fibers off the animals and clean them. They have a structure like human hair, with microscopic scales. If you apply a combination of moisture, heat, agitation and an additive like soap (modern) or whey (traditional), the fibers permanent interlace and mat together to form a sheet of fabric or a three dimensional item such as a tunic or hat. The resulting fabric is really warm, but doesn't have a lot of tensile strength. You fluff up the fibers, letting them lie in all directions. You roll them up in an old felt, called a 'mother felt' or in modern times a tarp. Apply friction and agitation, sometimes by dragging behind a horse. Eventually, the fibers bind together into whatever shape you choose. You can alter the shape as you go. This video is of traditional feltmakers in Iran. They aren't showing you much of the agitation portion of the process, but they do show in detail how a tunic is made without any seams or sewing at all. Even if you only watch the first few minutes of it, you will see a completely different methodology for how to create a garment. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d-WW39owXTE&fbclid=IwAR1FPhIxFdFewjnupdrLFCegmhBEC0etz7ZkURKZRaveHNhedXJbDtl7kSI Most of the cultures that created caftans thought of their materials as fabric; long narrow rectangles to be cut into geometric pieces and assembled with minimal waste. But as I had the opportunity to travel and get a close up view of many of these extant garments, there was a problem. Yes, rectangles and triangles and weird polygons under the arms were everywhere, cut symmetrically and systematically. But when you get really close to a lot of these garments, you start to see weird random pieces that appear out of nowhere. They seem to be added sort of ad hoc, not symmetrically, just wherever. It took me a remarkably long time to understand what was going on. Here's the thing: textiles produced by machinery really are endless rectangles with perfectly straight edges. But handwoven textiles are not. Every horizontal row of weft thread gets passed along by human hands, packed into place, pulled firmly along the edge and sent back in the opposite direction. And humans are not machines. There are variations not just in the width of a length of fabric, but also in how tightly packed each row is and good quality fabric has consistently packed rows. But even high quality handwoven fabric still has variations. Combine that fact with the expense of fabrics, particularly luxury fabric and people did whatever they had to do to get a complete garment. The conservator's report on the Caucasus caftan is hysterically funny to me because the brocade woven trim is of pretty terrible quality and the conservator's tone is one of indignation at just how uneven and badly woven it is. The theory is that the fabric may have been woven by indigenous weavers according to only a description of luxury foreign fabric seen by a high ranking member of the community and that it was woven on a tight deadline. Basically, the special occasion was almost there and the king was literally or figuratively standing in the weaving room yelling, "Weave faster!" So the motif starts out as evenly spaced circles and as the weaving progresses gets noticeably drawn out into extended ovals because the rows weren't being consistently packed. That results in the pattern repeats being inconsistent. So what we are seeing with all the weird piecing in the Ottoman caftans and other period caftans is that the tailor conceives of the fabric as being IDEALLY rectangular. And to compensate for the reality that it is not, uses irregular piecing to make the ideal geometric shapes. Basically, if the pieces making up each section (like the rectangle for the front left side, for example) aren't complete due to weaving issues or scarcity, the tailor adds pieces of whatever size and shape necessary to complete each section. Then the sections are sewn together. So when you are looking at the pattern diagram for an extant caftan there are two types of pattern pieces. There are the major pieces: large, structural, symmetrical, regularly geometric, cut on grain, and generally repeated from one caftan to the next. Some examples include rectangles or wedges for fronts, backs and sleeves, and triangles or wedges for gores in the sides or front. The second type are small, asymmetrical, frequently cut without regard to pattern or grain line, and frequently unique to the particular caftan. [At first glance you might think the gussets under the arms are in the second category, but they are actually in the first. Because while they are small and frequently cut without regard to grain, they are functional, necessary and symmetrical on the two sides of the garment] So the question becomes, when you recreate a garment, are you obliged to include the second category? These pieces only exist because of scarcity, or a 'defect' or irregularity in the fabric. All fabric of the time, all hand-woven fabric has irregularities. It's important to understand the strategies that were used to compensate, both to understand what you are looking at and as a tool for when you are confronted with similar problems in your own projects. However, because the second type of pattern pieces do not effect the fit, shape, drape or function of the garment, I don't see a compelling reason to include them unless you are deliberately recreating a particular garment. So for the caftan project, I plan to include these pieces as they occur in the individual garments but I don't plan to start making random patchwork a part of my general garment production strategy because it serves no useful purpose. I hope this provides some food for thought, please let me know what you think in the comments. and It's one of the most famous Ottoman caftans, it shows up in most books on Ottoman art and I've loved it forever. The ornament of crescents and tulips is huge in scale and amazing and characteristic of a deliberate Ottoman movement to differentiate Ottoman design from the broader background of Central Asian textile design.(Book recommendation: if you want to know more about how Ottoman textile design became distinctly Ottoman read this: The Sultan's Garden: The Blossoming of Ottoman Art This caftan is unusual in that the ornament is appliqued onto the crimson ground fabric instead of being woven in like most other examples. So it's an example of all the design elements that make Ottoman design distinctly Ottoman, but it is also unusual. This caftan makes a wonderful jumping off point for giving you an analysis of the all the Ottoman caftan patterns I've gotten to see. We have more extant caftans from the 15th and 16th century Ottoman Empire than pretty much anywhere else so we have the opportunity to compare more examples and see what general cutting patterns and sewing techniques show up most often and how they change across time and space. This particular caftan was exhibited widely in the 1980s before museum professionals understood the damage bright lighting does to textiles and so it is a sad echo of its former glory. Although the Turkish government is currently having it conserved and restored, so I have hopes... This is what it looks like currently. It makes my heart hurt. So I am working from multiple photos as well as my pattern notes, photos and diagrams from many other caftans of the same Ottoman 16th royal workshop provenance. Basically I'm using this particular reconstruction as a way to analyze and categorize 16th century Ottoman caftan patterns. And I get to do lots of applique, which I adore. I was able to find really good red silk taffeta, and more astonishingly, good silver silk taffeta. Studio update: what I'm working on Etsy shop link I love being a merchant in the SCA, I really, really do. But one of the side effects is that Christmas becomes a sort of 'bump in the road on the way to' whatever the first big event of the season is. In this case, Gulf Wars. Last year was really great for me as a merchant, but I went in woefully under-stocked, particularly on garments and hats. So I've been working like crazy on hats, and on garments to a lesser extent. I've gone down a Byzantine rabbit-hole, thanks to research I did to make a Laurel hat for my SCA sister Kerstyn So there were a couple of results of this rabbit hole. I've added this Byzantine 'halo' style hat with the temple pendants as well as the framed pillbox style, also with temple pendants. Also, my research has really focused on the Silk Road across Central Asia and parts south. The crazy Caucasus caftan (you will be hearing lots more about this amazing thing later) got me interested in how Eastern Europe connects to the Silk Road. Looking at all these Byzantine images led me to seeing other connections with northern Asia, and connections among Russia, Eastern Europe, the Byzantine Empire and the Silk Road. For years, I've said that the Persian taj that I make so many of are just Persian because that's the documentation I had. Now I'm seeing all these connections with the Byzantine halo style and with later Russian kokoshniks. My current theory is that the kokoshniks developed under the combined influence of hat shapes from both the Byzantine and Persian cultural spheres. This is just the beginning of a research project for me, if you have opinions or sources you'd like to share, please comment on this post or send me a message. At the other end of the Silk Road, I've started making Mongolian hats again too. I used to make them a lot when I lived out west where it gets cold but didn't have much need for them in the south. I've got some really excellent vintage furs that are waiting to become more hat brims and I've dug out my felting supplies for wool Mongol and Viking hats. I've also made some Mongol temple pendants that will appear soon as well. It's been really fun working on the temple pendants from both ends of the Silk Road at the same time. The traditions developed independently and it's been interesting making comparisons about aesthetics, technique etc. I also acquired a couple of Indian-made garments that are brilliant. One is very Mongol... The other is so Byzantine it hurts. It was made in India for the Muslim market in Kuwait and it came out... Byzantine? I don't understand it, but I like it. Here's a link to the Etsy shop if you are interested. Jadi's Silk Road New skills/experiments: When I made the first couple of Byzantine halos, I used wire and pearl vinework from the bridal department of the local craft store. But of course, like re-enactors and crafty people everywhere I thought: Hey, I can do that. So I did. I've been experimenting with brass wire, real pearls and other gemstone beads and various glass beads and having a blast. Between this project and all the temple pendants I can legitimately say: I am running out of beads. I need more beads. Actually, literally NEED. Fortunately there is a bead show in Atlanta this weekend and I have a list. I've been to this show quite a few times and it's small but good. I also have a cool website to share. http://skinddragter.natmus.dk/ from the home page: "The website “Skin Clothing Online” is a collaborative project between the National Museum of Denmark, Greenland National Museum & Archives and Cultural History Museum in Oslo. Here you will find unique, high-resolution, 360 degree rotation photos and detailed information about the National Museum of Denmark’s and the National Museum of Greenland's collections of fur clothing from indigenous peoples in Greenland, North America, Siberia and North Scandinavia from 2500 BC to the present day." Advantage: lots of photos that show construction and technique. Disadvantage: not many firmly dated period garments. Wait, wut? Entire garments make of fish skins. I did not know such a thing was possible. I promise I will update next week and show you my bead show loot! I need more pearls. Lots. and. Lots. of. Pearls.

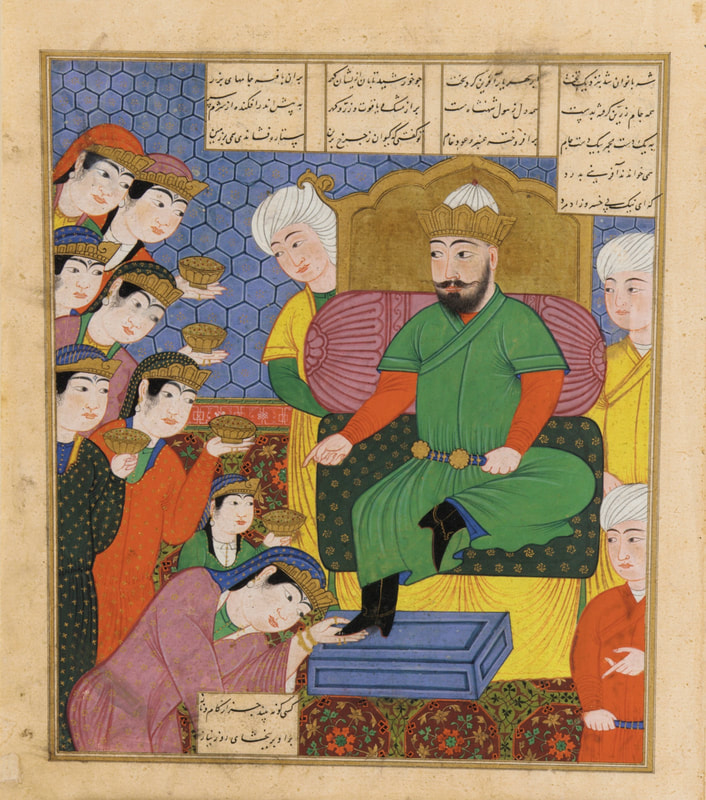

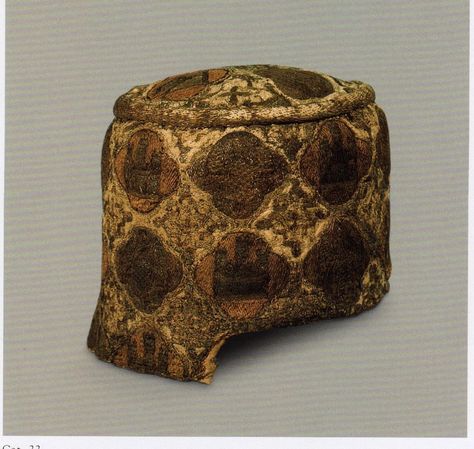

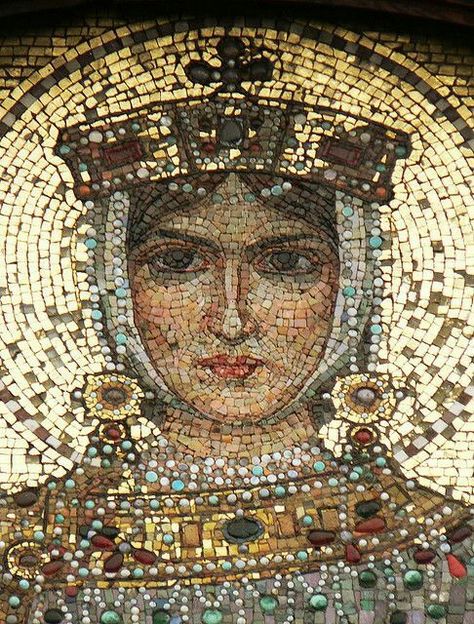

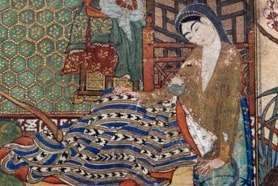

Hello everyone, I just wanted to let people know that I launched an Etsy shop, primarily for historic hats. Here is the link: JadisSilkRoad I love making hats because it's kind of an instant gratification project compared to whole garments (and whole books...sigh). I currently have two hat styles available; Persian tajs and Byzantine pillboxes and their variants. Below is a brief description and some photos of extant hats and artistic depictions. There is more information about the documentation of period hats in the description sections of the listings on Etsy. See how sneaky I am... Anyway: A lot of you will be familiar with the Persian taj or diadem style. I've made them and taught hands-on classes for ages but until recently all my documentation has been for Persia. However, plain tajs were worn in Roman times... ...and I'm beginning to see the same hat shape in Byzantine and Russian art. And, of all things, the Italian Renaissance. No seriously, check this out... The second hat style is a pillbox. I have recently realized that the pillbox hat is kind of like a T-tunic for your head, in that it appears all over the Old World across a huge time frame. There is a ton of variety, but that hat shape shows up in so many places and we actually have many extant examples. Some extant pillboxes are soft and flexible, others have a stiff frame. The ones currently on Etsy are the ones with the frames, with soft ones to follow. I have a new-to-me sewing machine with a ridiculous number of pre-programmed embroidery stitches and I think I want to cut out a bunch of soft pillboxes and put the machine through ALL of the stitches. There is even an elephant one. Anyway, framed pillboxes show up from Spain, across the Mediterranean and into the Byzantine empire and Russia. There are fewer examples in western Asia but there are some examples from the Turkic people and the Persians. I've also been using Pintrest to keep track of all the hat research, my username is Jadi Fatima. I'm not currently taking commissions for garments, but I will consider special orders for hats. Anyway, I hope this is useful for some of you, it would not hurt my feelings if you wanted to share the link to this blog post or the Etsy shop... Also, thanks for all the kind comments on the Caftan Book update, public and private. They soothed my soul and I feel so fortunate to be a part of this community. I hope all of your holiday plans unfold in precisely the way you wish them to, with an minimum of drama and an over-abundance of joy. I've been getting requests for an update on this project here and over at Kickstarter. You guys are right, it is overdue and I am sorry I haven't been more responsive. You deserve better.

There are two things going on that have led to the delays. First, there is the absolute avalanche of data. I have so much good information from other researchers as well as the huge amount of information I collected on my research trips, especially the month I spent in Europe examining garments. It's been hard to figure out where to draw the line for how to focus. There is so much raw information and I want it to be good. It has also been a difficult couple of years for me personally. I've been working a lot, and this year in particular has been a year of loss. I've lost two family members, five friends and my 17-year-old cat. At one point, three dear friends were all in active cancer treatment. Two of them continue their fight. A few weeks ago, one of my dearest friends lost his battle with cancer. He was my travel companion, research partner and guardian on the Europe trip that included his wife, a brilliant potter and ceramics historian who I call a sister. I am honestly shattered. I also know that he would be so mad at me if I let this loss and the others get in the way of this project, and art in general and my connections to the people I love. I've been in an electronic 'hibernation' for months because social media has amplified these losses we've suffered and that isolation needs to end. So that is the personal side, and if you'd like to say a prayer, pray for my friend Dennis and his beloved wife Teresa. His loss is vividly and widely felt. If you are in the SCA, his persona name is Master Mikal Halfdan of Meridies, master archer and most excellent cook. His wife is Mistress Kerstyen Gartenierin of Kerstyen's Zeramika So, on to the practical; The chapters for this book are of two kinds: pattern chapters and 'background' chapters like Textile Structures and History, Research Methods, and Historical Background Instead of making you wait until it's complete, I want to release two chapters at a time: one background and one that contains the analyis of one extant garment, complete with pattern and instructions. That way I can publish the information as I finish it as well as incorporate your feedback to make it as useful and interesting for you as possible. So I'm going to concentrate on a couple of chapters at a time. All of my Kickstarter backers will still receive a complete electronic and/or physical copy of the entire book at the end of the project as well as receiving the chapters before they go on sale to the general public. I also want to go ahead and fulfill the Kickstarter rewards that I currently can, which would be the reward level with the hats/headdresses. I'll be contacting you soon to let you choose the specifics. I want to thank everyone for all of the support and encouragement and patience. Many of you are dear friends, many of you are students and others of you have introduced yourselves to me at SCA events and I want to thank you for all of your kind words of support and encouragement, and most of all your feedback and questions and suggestions of reference materials. Thanks for your patience and understanding. I'll try to be worthy of them. Dennis would be really mad at me if I wasn't. My friend Leesa just asked me what I know about ikat fabric pre-1600 so I jumped at the chance to talk about one of my favorite kinds of fabric. Ikat is amazing and I am a bit obsessed with it. It's like hippie tie-die went to university and got a ph.d in physics. The basic process is this: all woven fabrics (as opposed to knitted, felted, twined etc) are formed by the intersection of threads under tension, with one parallel thread group situated at right angels to another. From a weaver's perspective as she weaves, the lengthwise threads are called the 'warp' and are held under tension. The weaver creates cloth by passing the weft thread in some variation of an over-under-over pattern to create cloth. So the simplest weave is an even number of warp and weft threads and the weft threads follow a pattern of under one, over one repeated. If you had that little plastic loom as a kid that came with fabric loops that you wove into a potholder, that is a basic plain weave fabric. But humans are clever and so there are an incredible number of techniques that have been used to add additional color, texture and pattern to cloth. Ikat creates a pattern by tie-dying the warp threads. Before they are put on the loom. Because the dyed pattern shifts a bit as the warp is set up on the loom and the weaving progresses, the patterns have 'fuzzy' edges. In Central Asia, the technique is called abr-bandi, which means 'cloud bands' or abrband meaning 'tying a cloud'. Ikat is also produced in Indonesia and that is where the term comes from, but for this post I am just talking about Central Asian abr-bandi. Here is a really brilliant article with gorgeous pictures of some of the steps: http://www.tafalist.art/ikat-weaving-cloud-tying-from-one-generation-to-the-next-in-uzbekistan/ So far, the earliest Central Asian ikat I have seen personally is from the 10th century. I'd like to push that back farther, if anyone knows of evidence that I'm missing, please share. This is a veil from 10th century Yemen. It has fringed edges and the calligraphic border was gilded in a similar way to the caftan worn by Hanzade Sultan that we were talking about a couple of days ago. This was likely the product of a workshop that made many of the same fabrics because there are at least three of these in the same colors and pattern in three different museum collections and they do not appear to be cut from one really large piece. (The Metropolitan Museum in New York, the David Museum and I can't remember the other one.) You do also see ikat depicted in Persian miniature painting a few hundred years later. They are almost always shown as night clothing or home furnishings like blankets. Ikat became really well known in the Western world in the 18th and 19th century when Central Asian weavers made the transition from small patterns, frequently arranged as stripes, to very large scale patterns. These larger patterns are stunning, and reminiscent of the Ottoman transition from small motifs to very large. Here is a link to a gorgeous slide-show of 18th-20th century ikat caftans that really show off the technical virtuosity of the weavers. https://www.hali.com/news/power-pattern-central-asian-ikats-david-elizabeth-reisbord-collection-lacma-los-angeles/#jp-carousel-24303 One of the things that really amazes me is that in the ikat industry in the Ferghana Valley in Central Asia (modern day Uzbekistan) the production of ikat is divided into up to 100 tasks from silk work to finished fabric. These tasks are then each controlled by a family-based guild. One to bind the warp, one to dye the warp, another to place it on the loom and another to do the actual weaving. Which makes sense when you think about it. I have also heard that this is still practiced in some of the villages there and that they loop the freshly-dyed warps along the outsides of the house overnight to dry. Can you imagine waking up with the dawn to watch the light dance over the silk? I don't know about you, but that is pretty high on my bucket list. The other tidbit I think is neat is that one of the preferred binding material for warps currently is the tape from cassette tapes. It has just a little bit of stretch so it allows the bindings to be wrapped tightly to more easily control where the craftsmen want the color to go. Simple string was used in period. Fortunately, the modern home decorator fabric market is currently obsessed with ikat, so it is easier to find. However, the modern 're-imagination' of traditional ikat uses the larger scale patterns and a mostly pastel color palette. That doesn't mean that you can't find good period-appropriate ikats for historical clothing, you just have to pay attention to scale and color. Also, ikat is still produced in places like Guatemala and Indonesia using cotton and with a more saturated color palette. Contemporary quilters are having a ball playing with ikats and indigo resist-dyed cottons in general, so if you have a quilt shop nearby, go check it out. I currently don't have solid documentation for the use of ikat in the clothing of people of high rank although I can find many examples of patterned stripes used by those of high rank. So I typically buy cotton ikat in smaller scale patterns and use them for field garb or as under-layers. Though I have a chunk of silk ikat that I can hear calling my name from the other end of the house. A couple more links:

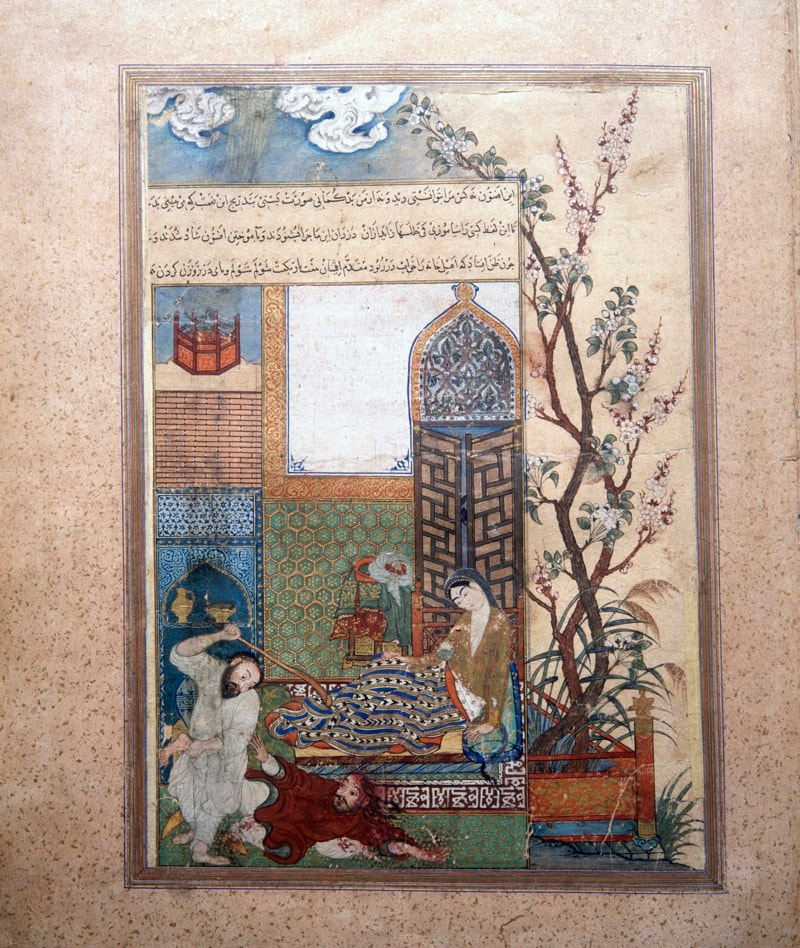

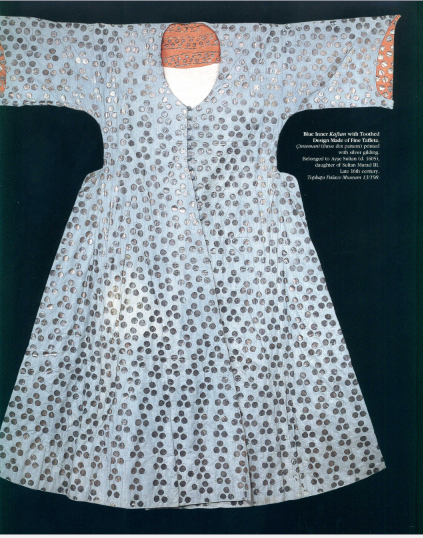

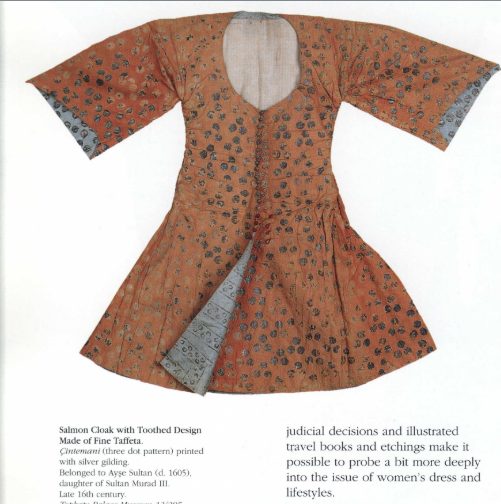

Global Ikat https://www.clothroads.com/ikat-the-world-over/ Types of Ikat https://www.clothroads.com/fooled-by-ikat/ I've been getting requests for a while about setting up an Etsy store and I've finally done it. It's called JadisSilkRoad. So far, I have all my available Persian tajs listed included the Laurel Wreath one and the Baronial Coronet. I'll be adding a few pieces of garb and some jewelry next. In working on the book the last few weeks, I've spent a lot of time looking at extant Ottoman caftans and I thought I'd share a few of the lesser known ones with you. The information and images about these caftans comes from: Tezcan, Hülya. Fashion at the Ottoman Court: The Topkapi Palace Museum Collection. Istanbul: Raffi Portakal, Portakal Art and Culture House Organisation, 2000. Print. This source also has excellent images of extant women's hats. One of the challenges of working with extant garments is the uneven way that historical garments have been saved, conserved, studied and displayed. Women's garments, even the garments of royal women, are less often conserved and displayed. So here are 3 extant Ottoman caftans. All 3 caftans were made for the daughters of Ottoman sultans. These garments were created for women who lived in the royal harem at the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul and that is where they have been conserved. They are identified as 'inner caftans', meaning they would have been worn over the gomlek (undergown), possibly in several layers based on the weather and the formality of the event. For formal occasions, an outer caftan of more precious fabric would have been worn as the final layer. And in bad weather, a ferace was worn as an overcoat. The first two caftans were made for Ayse Sultan, who was the daughter of Sultan Murad III; she died in 1605 In addition to details of cut and patterning, what fascinates me is that both caftans were made from the same two lengths of cloth, one with the blue fabric as the main fabric and one with salmon. I have no idea if these caftans were worn together or if the shorter salmon one was simply made up out of the remaining cloth leftover from the more formal blue one. Another interesting thing is that the silver dots are not applied by weaving, applique or embroidery but instead by gilding. The gilding process is the same for silk as it is for paintings on paper and we have several examples of this process on pre-1600 garments in Europe as well as Asia. So another question is: how common was this fabric? Did Ayse have the only two pieces or was this a more common pattern available either in the palace or more widely? The third caftan was made for Hanzade Sultan, daughter of Sultan Ahmed I. She died in 1650. This pink silk caftan was also made in the standard Ottoman style. There are also some interesting variations in cut, tailoring and possibly fit. The first two caftans were made for the same person. We don't know if they were made at the same time, just cut differently or if the garments were made separately as her body size and shape changed.

In addition to differences in length, the blue caftan has the 'bump out' shape at the top of the gores while the salmon one appears to have gores that are a simple triangle shape. Both of Ayse's garments have front gores that appear to start in the general vicinity of the waist. The garment made approximately 50 years later for Hanzade has a front gore that extends to the neck. It isn't clear from the way it is folded and displayed if Hanzade's had 'bump out' or traditional gores. The differences in gore style for both the front edge and the sides changes the way the garment fits and hangs as well as changing the silhouette by emphasizing or smoothing the hips. Another interesting thing is that if you just glance at the most famous extant Ottoman caftans, it appears that all garments had huge pattern motifs. However, this style of weaving was very complex and very expensive so it was reserved for people of very high status at very formal occasions. However, when you look at Ottoman paintings of figures where multiple layers of garments and many people of varying rank and it becomes apparent that the huge 'classically Ottoman' motifs were actually quite rare. Small motifs in the so-called 'international style' stayed fashionable, as did plain fabric and fabric with more subtle textured, stamped or woven effects. If that whole rabbit-hole intrigues you, start with the exhibit catalog for The Sultan's Garden: the Blossoming of Ottoman art. The entire exhibit and book are dedicated to explaining the shift from small motifs to large as a deliberate strategy to create a 'brand for' the newly emerging Ottoman empire. Absolutely fascinating and I was lucky enough to attend the symposium and exhibit tour led by Walter Denney and Nurhan Atasoy. https://museum.gwu.edu/sultans-garden-blossoming-ottoman-art https://www.amazon.com/Sultans-Garden-Blossoming-Ottoman-Softcover/dp/0874050375/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1544883462&sr=1-2&keywords=sultan%27s+garden Yikes, I didn't realize this book had gone up in price like that. I recommend inter-library loan,but it really is amazing. It also has the only known Ottoman block printed textiles.  I feel like I don't post on here often enough and I think my problem is that I tend to write such long posts that they are easy to put off. So I want to disrupt that pattern by trying out some shorter posts where I limit myself to a single cool thing. And I'm constantly finding new cool things as I am writing the book. So we know that in the Ottoman empire some garments were made at home and some came from royal workshops. We also know that there were commercial tailor's shops and guilds. And we also know that humans are sometimes lazy. So a ferace is essentially an Ottoman overcoat. It was lined, sometimes with fabric and sometimes with fur and it featured facings on the edges of the garment at the neck, sleeves, center front and hem. Caftans were frequently bordered this way as well. (And I have some new information about how the borders were sewn. More on that in the book, or in another post.) In Fashion at the Ottoman Court, Taksin references municipal laws "in Istanbul, Bursa and Edirne dated 1502 but relying on laws from 1477, require that the fringe that crossed the front opening and the perimeter of a ferace's skirt could not be pasted with glue but had to be attached through sewing, as had been customary in earlier times." I love finding random stuff like this. It gives me a different perspective and that is a good thing. One of the main challenges with early Ottoman clothing research is that while we have a lot of extant garments, they are mostly ones that were made for high-ranking members of the court. And the ones that are chosen for display in museums and reproduced in books are the fancy, splashy, unusual complicated ones that were worn for very formal occasions. It's like if the only sources our descendants had for early 21st century clothing were things that were worn on the red carpet at the Academy Awards. Interesting, but hugely, massively skewed. So the glue laws makes me ask myself a bunch of questions. 1. How common was this practice, really? (The fact that legislation persisted in time and location tells me it wasn't just a law aimed at that jerk who has a shop near Galata Bridge) 2. Was it something that bothered people or did they just know that if you bought a garment at a particular price point that you needed to take the time to hand-sew the facings on yourself? 3. Could someone look at a garment being worn and be able to tell that it had cheap glued borders? 4. Did the glue saturate the fabric and soak through? 5. Did the glued border change the way the garment hung? 6. What kind of glue? 7. What price range are we talking about? Any thoughts, my darlings? (So this is what a 'short post' looks like, apparently.) |

Archives

February 2020

Categories

All

|