I have been in love with Cloud Collars since I first discovered Persian art. The painting at left is one of my favorites. I've made quite a few of them over the years, most of them now owned by other people. Here are a couple of photos.

I have felt a serious embroidery binge coming on for a while now and so I am in the planning stages of a pretty elaborate collar for myself.

We know that empires in Central Asia such as the Ottomans, Timurids and Safavids had royal design houses that created designs for everything from architecture, ceramics and book arts to textile arts. In the Ottoman Empire, the design house was known as the kitabkhana.

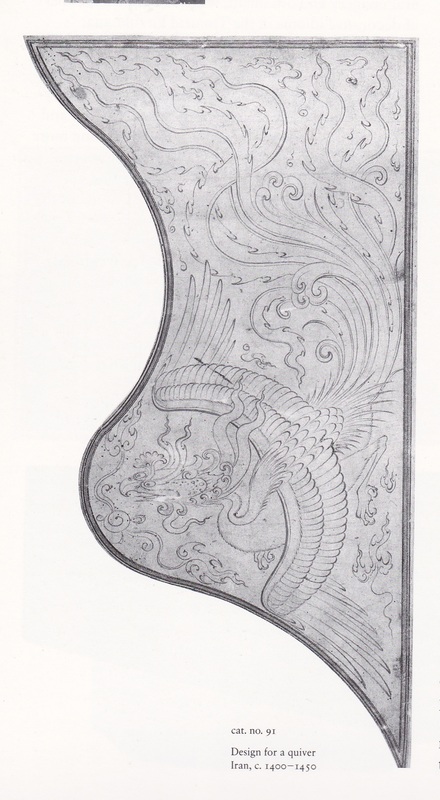

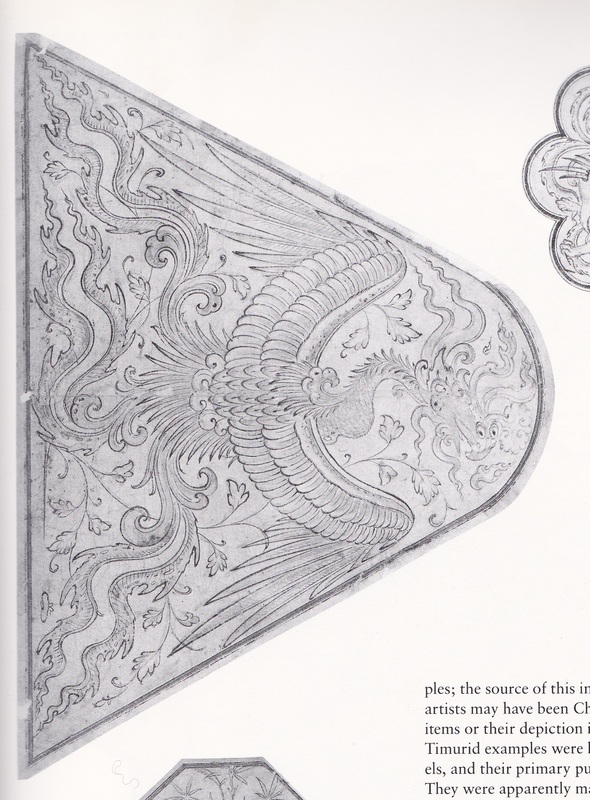

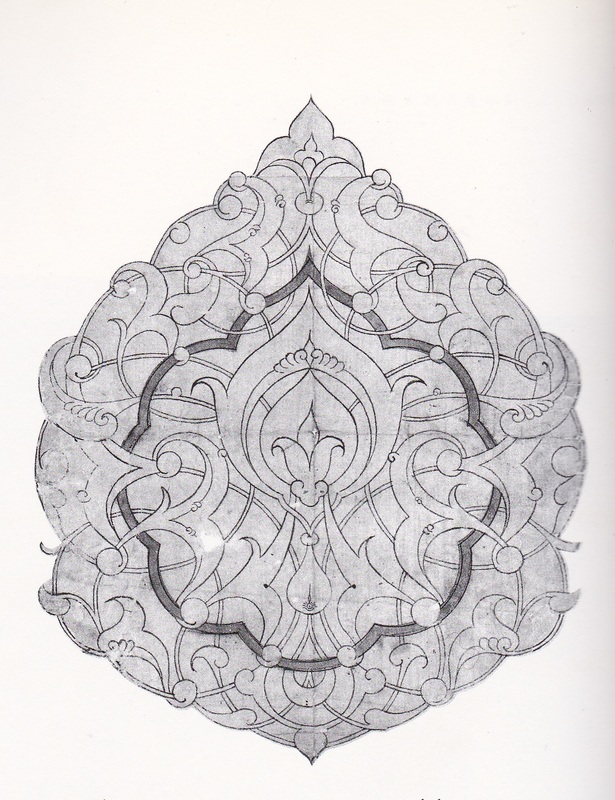

The designs were then given to craftsman to execute. Imagine my delight when I found reproductions of design sketches from the royal design house of the Timurids. My husband is used to these outbursts and is remarkably tolerant.

Some of these designs are specifically for cloud collars and some for other items such as quivers. They date from the first half of the 15th century, which is the time period during which my persona lived. In addition, the motifs include several that are of personal meaning to me, including lions and the simurgh or Persian phoenix.

I found them in the book Timur and the Princely Vision. This entire book is wonderful, by the way.

We know that empires in Central Asia such as the Ottomans, Timurids and Safavids had royal design houses that created designs for everything from architecture, ceramics and book arts to textile arts. In the Ottoman Empire, the design house was known as the kitabkhana.

The designs were then given to craftsman to execute. Imagine my delight when I found reproductions of design sketches from the royal design house of the Timurids. My husband is used to these outbursts and is remarkably tolerant.

Some of these designs are specifically for cloud collars and some for other items such as quivers. They date from the first half of the 15th century, which is the time period during which my persona lived. In addition, the motifs include several that are of personal meaning to me, including lions and the simurgh or Persian phoenix.

I found them in the book Timur and the Princely Vision. This entire book is wonderful, by the way.

We also have information on Persian embroidery. One of my main sources has been When Silk Was Gold, one of my other favorite books. There are photographs of extant embroideries and a very good chapter on how to do the embroideries.

There are extant cloud collars including one that is reproduced in a number of books including The Princely Vision and The Tsars and the East.

There are extant cloud collars including one that is reproduced in a number of books including The Princely Vision and The Tsars and the East.

This one has a little trick up its sleeve. It has undergone extensive restoration and not all books talk about this. The photo in the Princely Vision makes all the embroidery, including the background, appear to be gold and it is only briefly mentioned in the text. The photograph in The Tsars and the East (above) is of higher quality and the text includes a history of the piece, including its extensive restoration.

To summarize, the piece has been securely dated as 15th century Iranian, and was given as a royal gift to one of the Tsars which means that the design was likely produced by the same kitabkhana as the drawings in The Princely Vision. The original ground fabric was crimson silk and there are surviving fragments of the blue silk of the garment it was originally attached to.

The book identifies such a garment as 'a type of straight-cut Eastern robe without fastenings or collar', which is corroborated by the numerous paintings of figures wearing similar collars. The form of the collar follows what we see in paintings, except for the extended tabs down the front. I plan to omit those in the one I make.

The figures in gold and blue, the angels (peris), flowering vines etc were part of the original collar. The ground, which is actually of green silk is a 17th century restoration. This green silk was embroidered to imitate woven cloth and so in some inventories the collar is identified as having a green silk ground.

The loss of gold threads in the original motifs was replaced with gilt silver thread which has tarnished badly and some of the blue silks have been replaced as well.

So it was originally a blue silk garment with a red silk collar with gold thread embroidery with touches of blue. These are some of my favorite colors and I have all the materials I need to do this. I have a great piece of red silk taffeta for the ground and lots of gold threads. I also have a good supply of silk embroidery floss in blue, turquoise and red and I suspect I will use all of them.

To summarize, the piece has been securely dated as 15th century Iranian, and was given as a royal gift to one of the Tsars which means that the design was likely produced by the same kitabkhana as the drawings in The Princely Vision. The original ground fabric was crimson silk and there are surviving fragments of the blue silk of the garment it was originally attached to.

The book identifies such a garment as 'a type of straight-cut Eastern robe without fastenings or collar', which is corroborated by the numerous paintings of figures wearing similar collars. The form of the collar follows what we see in paintings, except for the extended tabs down the front. I plan to omit those in the one I make.

The figures in gold and blue, the angels (peris), flowering vines etc were part of the original collar. The ground, which is actually of green silk is a 17th century restoration. This green silk was embroidered to imitate woven cloth and so in some inventories the collar is identified as having a green silk ground.

The loss of gold threads in the original motifs was replaced with gilt silver thread which has tarnished badly and some of the blue silks have been replaced as well.

So it was originally a blue silk garment with a red silk collar with gold thread embroidery with touches of blue. These are some of my favorite colors and I have all the materials I need to do this. I have a great piece of red silk taffeta for the ground and lots of gold threads. I also have a good supply of silk embroidery floss in blue, turquoise and red and I suspect I will use all of them.

This embroidered canopy of gold simurghs is also going to serve as a model. It uses couched threads of a yellow silk core wrapped with a gilded paper substrate, made thick to 'achieve the effect of relief'. You can find this in When Silk Was Gold.

It's dated to Yuan period in China, 1279-1368. So it's a bit earlier than the rest, but the renderings of the simurghs is pretty constant through this period, so I'm using it to fill in technique details I can't get elsewhere. I've also made a test of the technique that is near the scale that will be used in my collar.

This was my first major attempt at gold-thread embroidery. My teacher, Lady Rouge from Caid (Las Vegas) suggested I use a finer gauge thread for something so small. It will be easier to get good detail.

It's dated to Yuan period in China, 1279-1368. So it's a bit earlier than the rest, but the renderings of the simurghs is pretty constant through this period, so I'm using it to fill in technique details I can't get elsewhere. I've also made a test of the technique that is near the scale that will be used in my collar.

This was my first major attempt at gold-thread embroidery. My teacher, Lady Rouge from Caid (Las Vegas) suggested I use a finer gauge thread for something so small. It will be easier to get good detail.

So this is the preliminary research. The next step is to scan and re-size the drawings so I can make a paper mock-up. Once I think I have the design in place, I'll do a test embroidery for a couple of the major motifs to make sure it will work like I think it will.

Then dressing the frame and embroidering. I do not plan to cut out the coat until the collar is done. I suspect this will take me most of the year, working on it for about an hour a day.

While I'm working on the design process for this collar, I'll be executing the embroidery for another, simpler collar for a friend of mine. I want to have that one done by March, for Gulf Wars. I'll be using that project to do some testing of techniques for this project as well.

I have some issues with insomnia and so part of my routine is to shut down all computer and tv screens a minimum of a half hour before I go to bed, as my doctor recommended. I've started working on soothing art projects during that period, so once the design and set-up phase is done, this will be my primary bedtime project.

Anybody else have any major projects planned for this year?

Then dressing the frame and embroidering. I do not plan to cut out the coat until the collar is done. I suspect this will take me most of the year, working on it for about an hour a day.

While I'm working on the design process for this collar, I'll be executing the embroidery for another, simpler collar for a friend of mine. I want to have that one done by March, for Gulf Wars. I'll be using that project to do some testing of techniques for this project as well.

I have some issues with insomnia and so part of my routine is to shut down all computer and tv screens a minimum of a half hour before I go to bed, as my doctor recommended. I've started working on soothing art projects during that period, so once the design and set-up phase is done, this will be my primary bedtime project.

Anybody else have any major projects planned for this year?