So, more good stuff from Valerie Hansen's The Silk Road: a new history.

So I mentioned how incredibly dry the Taklamakan region is, right? The average precipitation in one of the oasises is less than one inch per year. Less than an inch. In the oasis.

This incredible aridity means that lots of things enter the archaeological record here that wouldn't anywhere else.

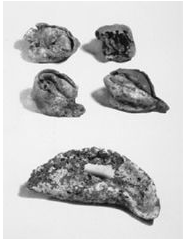

One of the finds that makes me particularly giddy is the food offerings from a tomb that have dried naturally and been preserved for 1500 years. Four wontons and a dumpling, you guys. Chinese dumplings that look like what you can order in restaurants all over the world. The archaeologists at the site noted that one of the wontons was broken open and they are pretty sure it was stuffed with pork and scallion. (The way I imagine this conversation playing out at the dig site is kinda hilarious.)

So I mentioned how incredibly dry the Taklamakan region is, right? The average precipitation in one of the oasises is less than one inch per year. Less than an inch. In the oasis.

This incredible aridity means that lots of things enter the archaeological record here that wouldn't anywhere else.

One of the finds that makes me particularly giddy is the food offerings from a tomb that have dried naturally and been preserved for 1500 years. Four wontons and a dumpling, you guys. Chinese dumplings that look like what you can order in restaurants all over the world. The archaeologists at the site noted that one of the wontons was broken open and they are pretty sure it was stuffed with pork and scallion. (The way I imagine this conversation playing out at the dig site is kinda hilarious.)

And in the same grave? Naan. Seriously, Indian naan flatbread. How cool is that?

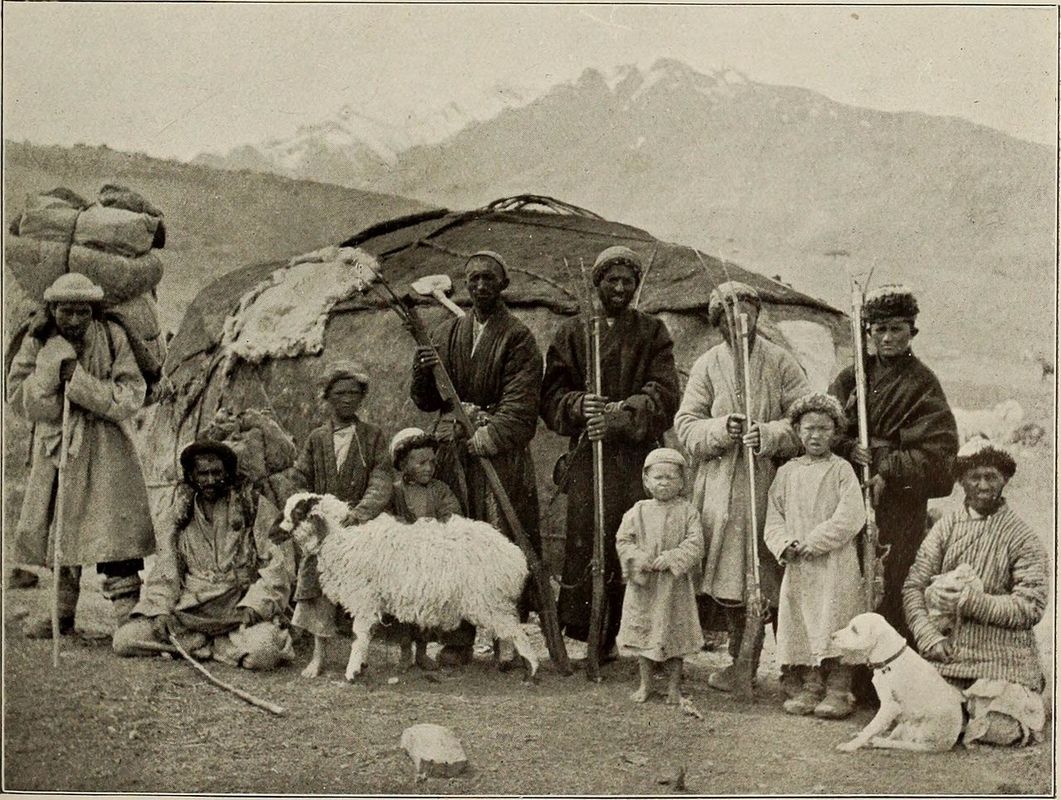

Where did the naan come from? It came with immigrants from the Gandhara region in India (including the modern cities of Bamiyan, Gilgit, Peshawar, Taxila, and Kabul in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan). Take a glance at a map, that's a pretty long and terrifying journey. From the city of Kashmir to the Kroraina kingdom in the Taklamakan Desert is almost a thousand miles and includes some of the highest mountain passes on the planet. Hansen calls this series of mountain ranges, known to geologists as the Pamir Knot, "a spiral galaxy of massive peaks radiating clockwise into the Karakorum, Hindu Kush, Pamir, Kunlun, and Himalayan mountain ranges."

Where did the naan come from? It came with immigrants from the Gandhara region in India (including the modern cities of Bamiyan, Gilgit, Peshawar, Taxila, and Kabul in modern Pakistan and Afghanistan). Take a glance at a map, that's a pretty long and terrifying journey. From the city of Kashmir to the Kroraina kingdom in the Taklamakan Desert is almost a thousand miles and includes some of the highest mountain passes on the planet. Hansen calls this series of mountain ranges, known to geologists as the Pamir Knot, "a spiral galaxy of massive peaks radiating clockwise into the Karakorum, Hindu Kush, Pamir, Kunlun, and Himalayan mountain ranges."

Aurel Stein, a Hungarian-British explorer and archaeologist, retraced this journey in the late 19th c. He was using the same technology and transportation used by the Ghandaran immigrants almost 2000 years earlier.

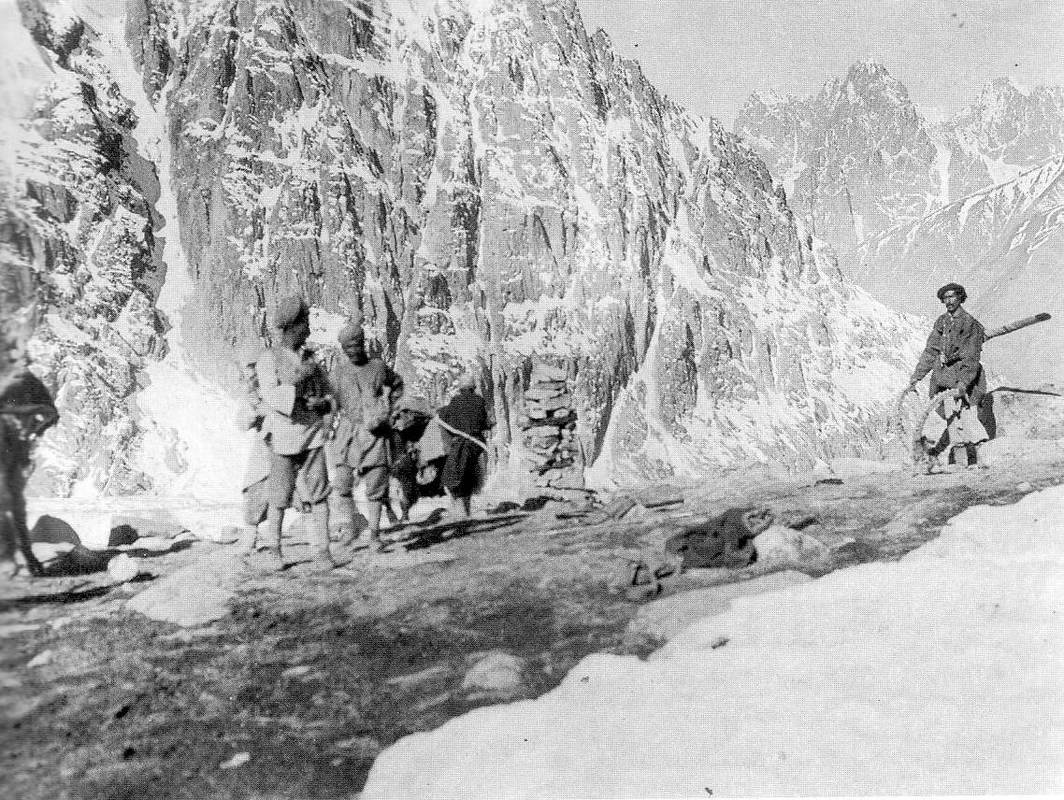

Hansen says, "Stein used a new route through the town of Gilgit that the British had opened only ten years earlier. He timed his crossing of the Tragbal Pass (11,950 feet, or 3,642 m) and Burzil Pass (13,650 feet, or 4,161 m) to occur in the summer after the snow had melted... He used human porters, as no pack animal could negotiate these tortuous trails. After crossing into China at the Mintaka Pass (15,187 feet, or 4,629 m), they proceeded north to Kashgar and from there to Khotan and then Niya. On some sections of the Gilgit Road, one can still see drawings and inscriptions left behind by ancient travelers on the rock walls. Travelers often had to halt for several months before they could proceed; like Stein, they had to wait for the snow to melt in the summer and could take desert routes only in cooler winter weather. During these lulls, they used sharp tools or stones to rub off metallic accretions and etch extremely short messages or simple sketches directly on the surface of the rock."

She also mentions that for some sections of passes the people walked along the sheer side of mountains using wooden pegs hammered into the stone cliffs as steps. Carrying full packs. Over sheer drops. I am the tiniest bit terrified of heights (I'm better now, ask me about circus school sometime...) and I cannot imagine trying to do that. Well, actually I can and I don't like it.

K

I love digging up the details for the different legs of the trip, it makes it feel real. There's a lot more awesome stuff in this book. Here's the link if you want your own copy.

One of the other things that caught my attention was descriptions of Kongque River, that is, the Peacock River. It's a river with naturally occurring metal deposits dissolved in the water, turning it into shades of brilliant peacock blue and green.

Here are some pictures of the river as it looks today.

Can you imagine coming down out of those impossibly high mountains, or from the dunes of the Taklamakan and seeing this?

I love digging up the details for the different legs of the trip, it makes it feel real. There's a lot more awesome stuff in this book. Here's the link if you want your own copy.

One of the other things that caught my attention was descriptions of Kongque River, that is, the Peacock River. It's a river with naturally occurring metal deposits dissolved in the water, turning it into shades of brilliant peacock blue and green.

Here are some pictures of the river as it looks today.

Can you imagine coming down out of those impossibly high mountains, or from the dunes of the Taklamakan and seeing this?